Article Structure

Why the Linga Is Often Misunderstood

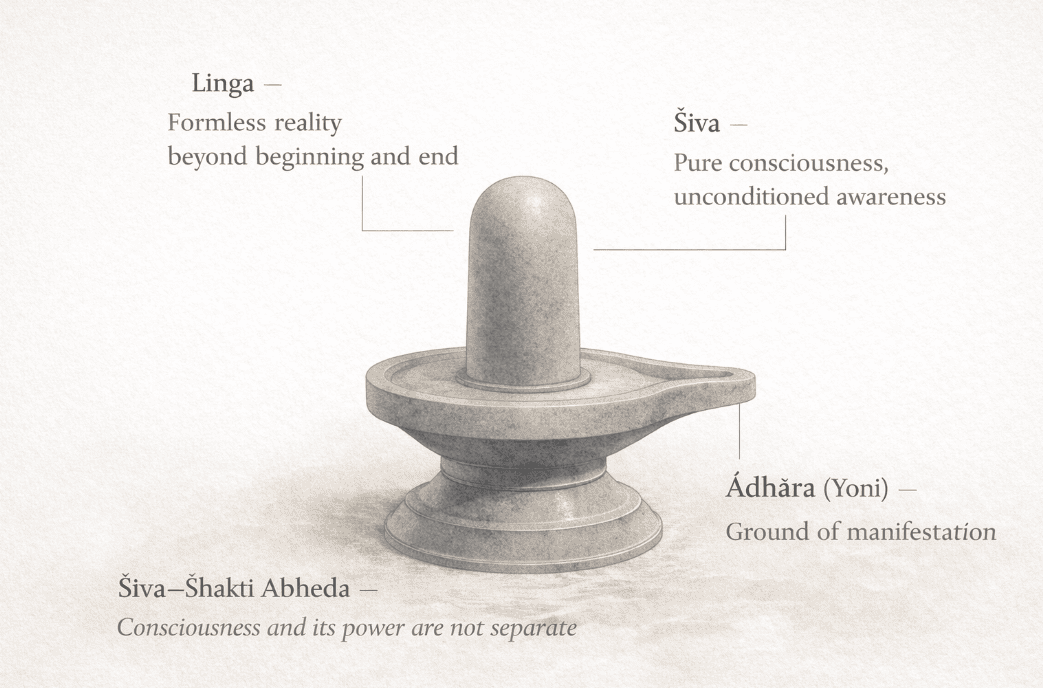

Among Hindu sacred symbols, the Shiva linga is one of the most widely recognized and most frequently misunderstood. Modern interpretations, especially outside India, often reduce it to a bodily or anatomical symbol. This view appears in popular media and some strands of Western scholarship, creating the impression that the linga represents a physical form.

Traditional Shaiva sources do not support this reading. When you examine the linga through scripture, ritual manuals, philosophy, and historical practice, a different picture emerges. The linga was never intended to represent a body. It functions as an aniconic marker of the infinite, pointing toward a reality that cannot be depicted through form.

Where the Linga Actually Comes From

The theological origin of the linga lies in the Lingodbhava narrative, described in texts such as the Shiva Purana and Linga Purana. In this episode, a boundless pillar of light appears between Brahma and Vishnu, extending endlessly in both directions. Neither deity can find its beginning or end.

This pillar, the jyotirlinga, is not presented as a body or figure. It is pure luminosity without boundaries. When Shiva reveals himself as its essence, the pillar becomes the symbolic reference point for the linga that later appears in temples.

The linga is therefore not a representation of Shiva’s form. It is a stylized memory of infinity, reduced into a stable symbol that allows contemplation without anthropomorphism.

Why the Linga Was Never Given a Face or Form

One of the clearest indicators of the linga’s intent is its design.

The linga has:

- No face

- No limbs

- No posture

- No narrative gesture

Shaiva Agamic texts consistently describe the linga as nirakara, formless. The Kamika agama, one of the core Shaiva ritual texts, defines it as a vertical axis representing unmanifest reality.

The base, commonly called the yoni, is also frequently misunderstood. In Shaiva interpretation, it functions as a cosmic support, symbolizing dynamic energy (sakti) that enables manifestation. Together, the linga and base form a cosmic axis, not an anatomical reference.

How the Body-Based Interpretation Took Hold

The bodily interpretation of the linga does not originate within classical Shaiva traditions. It emerged primarily during the colonial period, when European scholars attempted to explain Hindu symbols using comparative frameworks drawn from other cultures.

Writings from the 18th and 19th centuries often projected fertility symbolism onto the linga, drawing parallels with Greco-Roman cults while overlooking indigenous explanations. Later interpretations influenced by psychoanalytic theory reinforced this framing, prioritizing erotic symbolism over metaphysical intent.

While these interpretations explored one layer of symbolism, they often ignored explicit scriptural statements that describe the linga as beyond form and embodiment.

What Shaiva Texts Say When You Read Them Closely

Indian philosophical texts consistently move away from bodily description when discussing ultimate reality.

The Upanishads describe the divine using negation rather than form. The Svetasvatara Upanishad speaks of Rudra as all-pervading and formless, present without physical limitation. This approach shapes later Shaiva theology.

Shaiva Siddhanta philosophers describe the linga as a subtle focus point, allowing the mind to settle on what cannot be seen. It is not a body, but a support for realization.

In Kashmir Shaivism, the linga is associated with spanda, the subtle vibration of consciousness itself. This vibration is experiential, not visual or anatomical.

What the Oldest Lingas Actually Look Like

Material evidence supports this interpretation.

Early linga forms, including those associated with the Indus Valley civilization, appear as simple stone pillars, lacking any human or divine features. These objects predate classical iconography and reflect early symbolic practices centered on natural forms.

Later temple installations continue this abstraction. Lingas placed in sanctums serve as the focal point for ritual bathing, not visual storytelling. Even at the twelve jyotirlinga sites, emphasis falls on presence and continuity, not embodiment.

What Happens During Linga Worship

Ritual practice reinforces the linga’s abstract role.

During linga puja:

- Offerings are directed to the absolute, not a personal form

- Mantras invoke elemental and cosmic principles

- Proportions follow geometric and mathematical ratios

Unlike murti worship, which engages narrative and emotion, linga worship encourages interiorization. The symbol does not invite identification with a form. It invites awareness of what lies beyond form.

Why Creative Language Does Not Mean Physical Meaning

Some texts describe the linga using creative metaphors. These passages are often cited to argue for bodily symbolism. Within Shaiva tradition, such language is understood metaphorically.

Creation here refers to manifestation, not reproduction. The Linga Purana itself clarifies that the linga is avyakta, unmanifest. Creative imagery functions as philosophical language, not anatomical description.

Scholars working within Shaiva frameworks emphasize that interpreting these metaphors literally distorts their intent.

How Different Shaiva Traditions Understand the Linga

The abstract meaning of the linga remains consistent across Shaiva schools.

In Virashaivism (Lingayatism), devotees wear a small personal linga as a reminder of inner divinity. It is not treated as a bodily symbol, but as a marker of awareness and equality.

In Pasupata Shaivism, the linga represents liberation from cycles of rebirth, not embodiment. Across traditions, the symbol points inward rather than outward.

Why This Confusion Still Shapes Modern Perceptions

Modern misreadings of the linga often reduce a complex philosophical symbol into a single physical idea. Reclaiming its original meaning is not about defensiveness. It is about accuracy.

When the linga is understood as an aniconic symbol of the infinite, its role in Hindu practice becomes clearer. It represents a tradition that chose abstraction over depiction, realization over representation.

What the Linga Was Pointing To All Along

The Shiva linga was never designed to depict a body. It was designed to remove the need for depiction altogether.

As a symbol, it stands for:

- That which has no beginning or end

- That which cannot be described through form

- That which is realized, not visualized

Understanding the linga in this way restores its original theological purpose: not as an object of interpretation, but as a gateway to the formless.