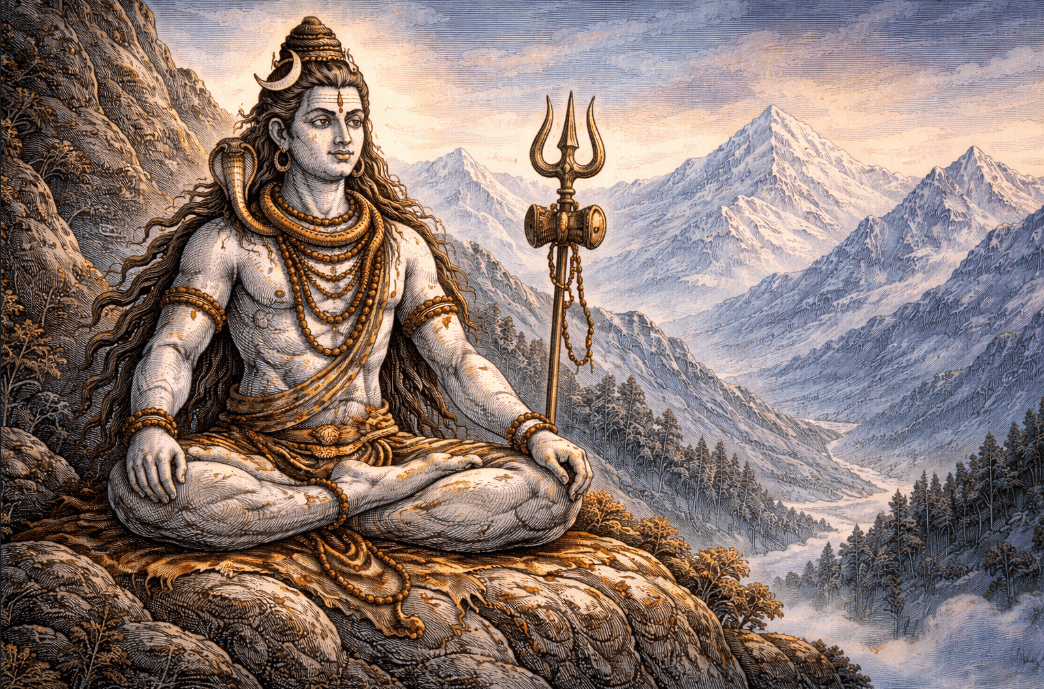

Lord Shiva, carries an array of profound symbols in his iconography, each conveying layers of cosmic and spiritual truth. Among these, the crescent moon resting upon his head, often nestled in his matted locks (Jata), stands as one of the most evocative. Known as Chandrashekhara (the one who wears the moon as a crest), Shiva adorns this celestial body instead of a royal crown of gold or jewels. A crown typically signifies earthly sovereignty, dominion over kingdoms, and material authority. The crescent moon, by contrast, embodies serene mastery over impermanence, controlled cycles of time, mental tranquility, enlightenment, and cosmic balance.

This deliberate choice reflects Shiva’s transcendent nature: he governs the universe not through imposed regal power but through effortless equilibrium and inner realization. The crescent moon, never full, always partial, symbolizes controlled change rather than static glory. This article examines the reasons behind this adornment, supported by narratives from the Shiva Purana, other Puranic texts, and Shaiva philosophical interpretations. It explores mythological origins, symbolic dimensions, and practical relevance for spiritual seekers.

Article Structure

The Primary Myth: The Curse of Daksha and Chandra’s Refuge

The most widely recounted legend explaining the crescent moon’s presence on Shiva’s head centers on Chandra (the moon god, also called Soma) and the curse pronounced by Daksha Prajapati.

Chandra married the twenty-seven daughters of Daksha, each representing one of the lunar mansions (nakshatras). However, he showed marked favoritism toward Rohini, neglecting the others. Offended by this partiality, Daksha cursed Chandra to lose his radiance gradually until he faded into complete darkness. As the moon began to wane daily, cosmic imbalance ensued: tides disrupted, plants suffered, and living beings experienced distress due to the absence of lunar light and cooling influence.

Desperate, Chandra sought counsel from Brahma, who advised that only Shiva possessed the power to mitigate such a curse from a Prajapati like Daksha. Chandra performed intense penance at Prabhasa Tirtha (near the Sarasvati River), constructing a lingam and chanting prayers for six months. Pleased by his devotion, Shiva appeared and explained that Daksha’s words carried irrevocable weight, yet he could offer partial relief.

Shiva declared: during the dark fortnight (Krishna Paksha), Chandra would wane, diminishing to a crescent; during the bright fortnight (Shukla Paksha), he would wax, regaining fullness. To ensure protection and perpetual balance, Shiva placed the crescent moon upon his own head. This act not only stabilized Chandra but established the eternal lunar cycle of waxing and waning. The Shiva Purana describes this as Shiva becoming the eternal guardian of time’s rhythm, with the crescent serving as a visible emblem of cosmic regulation.

In some variants found in texts like the Bhagavata Purana and Mahabharata references, the intervention follows Chandra’s plea after the curse threatened universal harmony. Shiva’s compassionate acceptance underscores his role as protector of even celestial beings, transforming a potential catastrophe into ordered periodicity.

Alternative Narratives: Cooling After the Halahala Poison

Another significant account links the crescent moon to the Samudra Manthan (churning of the cosmic ocean). During this event, halahala poison emerged, threatening all existence. Shiva swallowed it to safeguard creation, holding it in his throat (earning the name Neelkantha). The venom’s heat caused intense burning.

To provide relief, the gods, including Chandra, offered cooling aid. The moon’s inherently soothing, nectar-like (amrita-dripping) quality made it ideal. Shiva accepted the crescent on his head, where its rays and cooling essence alleviated the poison’s effects. The Padma Purana mentions the moon exuding amrita to bathe Shiva, countering Vasuki’s (the serpent around his neck) heat.

This narrative complements the Daksha story: both portray the moon as a source of tranquility and renewal, placed on Shiva’s head to maintain his equanimity amid cosmic duties.

Symbolic Dimensions: Controlled Time Cycles and Impermanence

The crescent moon primarily symbolizes mastery over time (kala). Unlike the sun’s constant radiance, the moon’s phases illustrate impermanence: birth (waxing), fullness, decay (waning), and renewal. Shiva, as Mahakala (the great time), transcends yet regulates these cycles. By wearing the crescent, not the full moon, he demonstrates controlled dominion over temporality. The Shiva Purana states: “Shiva, the Supreme Lord, is the controller of time itself. The crescent Moon on His forehead symbolizes the eternal cycle of time.”

This contrasts sharply with a royal crown, which denotes fixed, worldly authority. Crowns represent accumulation and permanence in material realms; the crescent embraces flux, reminding that all phenomena arise, endure briefly, and dissolve. Shiva’s serene acceptance of the crescent affirms his sovereignty beyond birth and death, eternal reality governing transient forms.

In Shaivism, time manifests as cyclical: srishti (creation), sthiti (preservation), samhara (dissolution), tirobhava (concealment), and anugraha (grace). The lunar phases mirror this, with Shiva’s head placement indicating oversight from the highest consciousness.

The Moon as Mind and Mental Stillness

In Hindu philosophy, the moon represents the mind (manas). Just as the moon waxes and wanes, thoughts fluctuate, rising in passion, peaking in clarity, declining into confusion. Uncontrolled, the mind leads to suffering; mastered, it fosters peace.

Shiva’s placement of the crescent on his head signifies perfect control over the mind. The waning aspect denotes detachment from ego and desires; the waxing, renewal through awareness. Philosophical interpretations, including those in Kashmir Shaivism, view the crescent as a symbol of reduced ego (minimal mind required to express the inexpressible no-mind state). Sri Sri Ravi Shankar explains: wisdom transcends mind, yet requires a trace of it for manifestation, hence the partial moon.

This contrasts regal crowns, which often symbolize ego amplification through status. Shiva rejects such vanity, choosing serene mastery: inner calm amid external change.

Enlightenment and Cosmic Balance

The crescent moon further signifies enlightenment. Its soft light illuminates darkness without overwhelming glare, akin to gradual spiritual awakening. Placed near Shiva’s third eye in some depictions, it links to intuitive wisdom piercing illusion.

In Ardhanarishvara form (Shiva-Shakti union), the moon complements feminine nurturing energy, balancing Shiva’s ascetic fire with lunar coolness. It represents harmony: masculine-feminine, destruction-creation, stillness-motion.

Devotees see it as a reminder of immortality’s nectar (amrita): the moon drips sustaining essence, symbolizing Shiva’s role in granting moksha beyond cycles.

Artistic and Historical Depictions

The crescent moon’s iconography evolved prominently from Gupta (4th-6th centuries CE) to Chola periods (9th-13th centuries CE), appearing in bronzes, temple carvings, and paintings. It consistently occupies the right side of Shiva’s matted locks, above the forehead, emphasizing subtlety over ostentation.

Epithets like Chandrashekhara and Chandramouli underscore this feature across Shaiva literature.

Meaning for Contemporary Seekers

In modern practice, the crescent moon inspires reflection on impermanence: attachments fade like waning light, yet renewal follows. It encourages mental discipline through meditation, observing thoughts without identification.

Rituals on full moon (Purnima) or new moon (Amavasya) invoke lunar energy for tranquility. Wearing moon-related symbols or chanting mantras like “Om Chandraya Namah” aligns practitioners with Shiva’s serene mastery.

The symbol counters materialism: while crowns signify worldly power, the crescent teaches detachment, true authority arises from inner balance, not external adornment.

The Crescent Moon as a Symbol of Balance

Shiva wears the crescent moon instead of a royal crown because it expresses a deeper form of sovereignty. Through myths of Daksha’s curse and the halahala poison, the moon emerges as a symbol of regulated time, mental stillness, renewal, and cosmic balance.

Unlike a crown’s fixed opulence, the crescent celebrates impermanence under awareness. It reveals Shiva as ruler not through domination, but through equilibrium.

In this quiet celestial arc rests a profound truth: ultimate authority lies in mastering change, calming the mind, and remaining rooted in the eternal amid the cycles of becoming. Shiva’s adornment thus points not to kingship, but to liberation.