In the profound tapestry of Hindu cosmology, Sadashiva emerges as the paramount manifestation of the divine, embodying the eternal and absolute essence beyond the cycles of creation, preservation, and destruction. Revered in Shaiva traditions as the Para Brahman, the ultimate reality, Sadashiva represents the luminous, subtle absolute that precedes all forms and functions in the universe. This revelation of Sadashiva is not merely a mythological event but a metaphysical truth articulated across ancient scriptures, signifying the first emanation from the formless Parashiva. Drawing from the Vedas and Puranas, this exploration delineates the scriptural foundations, mythological narratives, philosophical implications, and iconographic representations of Sadashiva’s inaugural appearance, underscoring his role as the originator of cosmic order.

Article Structure

Vedic Foundations: Rudra as the Precursor to Sadashiva

The Vedas, the oldest sacred texts of Hinduism, lay the groundwork for understanding Sadashiva through the figure of Rudra, an early Vedic deity who evolves into the multifaceted Shiva in later traditions. In the Rigveda, one of the four principal Vedas, Rudra is invoked in several hymns that highlight his dual nature, fierce and benevolent, foreshadowing the comprehensive attributes of Sadashiva. For instance, Rigveda Hymn 10.92 describes Rudra as possessing two contrasting aspects: one wild and cruel (rudra), and another kind and tranquil (shiva), which aligns with Sadashiva’s eternal auspiciousness. This duality suggests an initial revelation of divine power that transcends mere destruction, encompassing grace and prosperity.

Specific hymns dedicated to Rudra in the Rigveda, such as 1.43, 1.114, 2.33, and 7.46, comprising 39 verses, portray him as a celestial deity associated with storms, healing, and protection. In Rigveda 1.43, Rudra is declared the “conscious knower,” encapsulating his omniscience and role as a divine contradiction, both destroyer and healer, which mirrors Sadashiva’s five-fold functions in later Shaivite philosophy. The Sri Rudram from the Yajurveda further elevates Rudra as “Sadashiva,” one of the eleven epithets, meaning “always kind, happy, and prosperous.” This Vedic invocation marks the nascent revelation of Sadashiva, where Rudra is not yet fully differentiated but embodies the seeds of the supreme form that would be elaborated in the Puranas.

Philosophically, these Vedic references position Sadashiva’s first appearance as an intrinsic aspect of the cosmic consciousness, predating structured creation. The absence of explicit iconographic descriptions in the Vedas indicates that Sadashiva’s revelation was initially conceptual, revealed through hymns to sages who perceived the divine through meditation and ritual. This sets the stage for the Puranic expansions, where Sadashiva assumes a more tangible, albeit symbolic, form.

Upanishadic Clarity: The Supreme Principle Revealed

The Upanishads provide the philosophical framework that makes the idea of Sadashiva’s “first appearance” intelligible.

Shvetashvatara Upanishad

The Shvetashvatara Upanishad explicitly associates Rudra-Shiva with the supreme reality. It states that Rudra:

- Exists before gods

- Is the cause behind causes

- Is beyond time and form

This text does not describe an event where Shiva appears. It describes a moment of recognition, where ultimate reality is identified and named.

Sadashiva, in this context, is not a later invention. He is the named articulation of an already-present absolute.

Mythological Accounts of Origin

The Puranas, expansive narratives composed between the 3rd and 16th centuries CE, provide detailed accounts of Sadashiva’s first appearance, transforming Vedic abstractions into vivid mythological episodes. Central to these is the Padma Purana, particularly the Patala Khanda, Chapter 108, which explicitly declares Sadashiva as the originator of the Trimurti, Brahma, Vishnu, and Maheshwara (Shiva). In this chapter, while explaining the origin of sacred ash (vibhuti), Lord Rama inquires about its significance, prompting Sambhu (Shiva) to narrate Sadashiva’s primordial act.

According to the text, the eternal Sadashiva, described as three-eyed, beyond qualities, and unchangeable, desired to create upon perceiving the three gunas (qualities) within himself, sattva (goodness), rajas (activity), and tamas (ignorance), equated to the three Vedas. He divided himself and the cosmic region, manifesting Brahma from his right side, Vishnu (Hari) from his left, and Maheshwara from his back. Upon their birth, the three deities questioned their identities, to which Sadashiva proclaimed himself their father and assigned the gunas: sattva to Brahma for creation, rajas to Vishnu for preservation, and tamas to Maheshwara for destruction. This narrative reveals Sadashiva’s first appearance as a self-division, establishing him as the supreme source from which the functional gods emerge, emphasizing his transcendence over the Trimurti.

The Shiva Purana, a key Shaivite text, further elucidates Sadashiva’s revelation in the Rudrasamhita section. Here, Sadashiva is portrayed as the father of Shiva, Brahma, and Vishnu, manifesting as a linga, a symbolic form, for worship, as the abstract absolute requires a concrete representation for devotion. In Shiva Purana 2.2.36, Sadashiva is described as a form of Shiva knowable through devotion and mental tranquility, highlighting his luminous essence. This appearance underscores the transition from formless (nishkala) Parashiva to the manifest Sadashiva, facilitating cosmic activities.

In the Linga Purana, dedicated to the worship of the Shiva Linga, Sadashiva’s revelation is tied to the glory of his five faces. Chapter 11 extols Sadyojata, one of Sadashiva’s faces, as the western-facing aspect embodying moon-ray color and associated with creation. The text describes Sadashiva as the prop of virtues, residing in the Sadakya Tattva, and performing the five cosmic acts through deputed lords: creation (Brahma), preservation (Vishnu), destruction (Rudra), obscuration (Maheshvara), and grace (Sadashiva himself). Chapter 89 on good conduct (sadacara) invokes Sadashiva in rituals, linking his appearance to ethical living and linga worship.

The Brahmanda Purana reinforces this in sections like III.56.17 and IV.8.33, where Sadashiva is worshipped at sacred sites like Gokarnam, signifying his eternal presence revealed through pilgrimage and devotion. Similarly, the Vayu Purana (62.32) names Sadashiva as a form of Vighneshvara, integrating him into broader Puranic lore. These accounts collectively depict Sadashiva’s first appearance as a revelatory act of self-manifestation, initiating creation while remaining beyond it.

SadaSiva Philosophical Significance

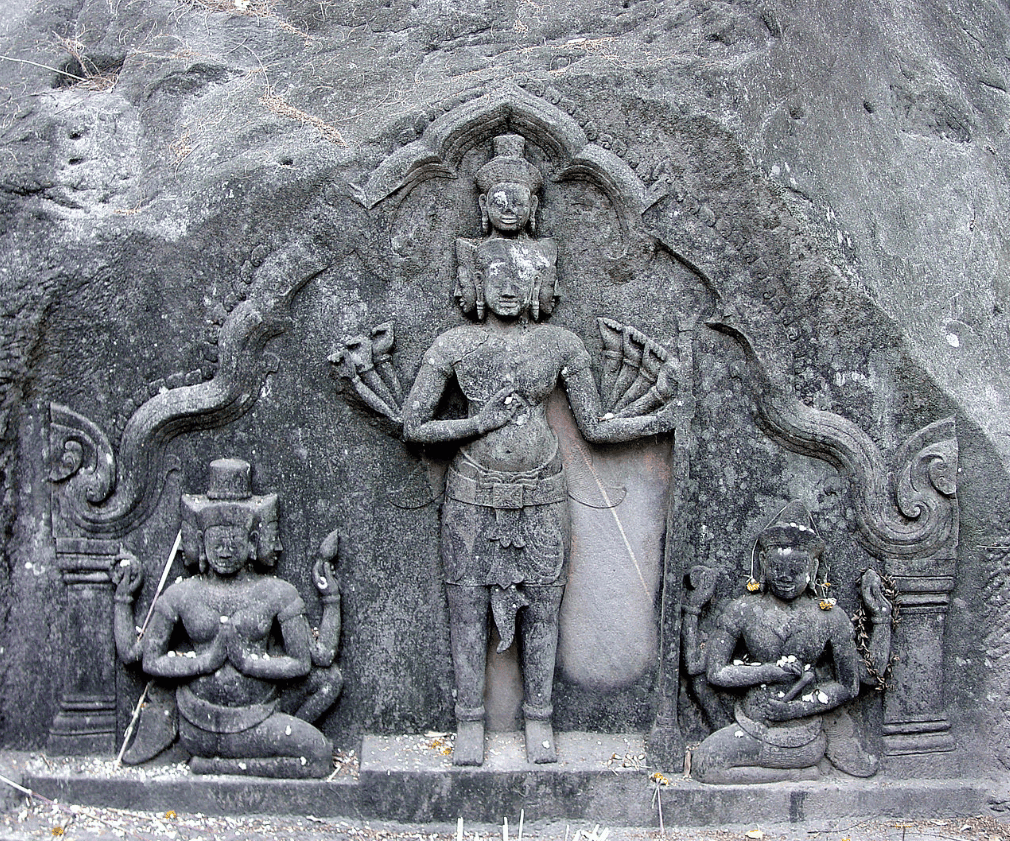

Philosophically, Sadashiva’s revelation in the scriptures embodies the Shaiva Siddhanta doctrine of Panchakritya, the five holy acts: creation, preservation, destruction, obscuration (tirodhana), and grace (anugraha). As the highest form, Sadashiva specifically governs grace and obscuration, liberating souls from bondage (pasha). His five faces, Ishana (upward, crystal), Tatpurusha (east, whitish-yellow), Aghora (south, blue-black), Vamadeva (north, saffron), and Sadyojata (west, moon-ray), represent the Panchabrahmas, emanations from Parashiva, each directing a cosmic function. This pentadic structure expands the Trimurti concept, positioning Sadashiva as the integrator of all realities.

Iconographically, Sadashiva is depicted with ten arms symbolizing the ten directions, holding attributes like the trishula, axe, and damaru, seated with his consort Manonmani. The earliest known sculpture, a five-faced lingam from Bhita near Prayagraj, dates to the 2nd century CE, marking the historical revelation of his form. Texts like the Kamika Agama and Vishnudharmottara Purana prescribe this imagery, emphasizing the mukhalinga as Sadashiva’s subtle representation.

In Agamic texts such as the Rauravagama (3.53.2-3) and Mrigendragama, Sadashiva is the vidyadeha form revealing Vedas and Agamas through mantras. The Netratantra (verses 9.5-11) describes him as composed of five brahmamantras, underscoring meditative revelation. This philosophical depth reveals Sadashiva not as a temporal event but as an eternal truth accessible through devotion.

SadaSiva Historical and Comparative Contexts

Historically, Sadashiva’s originated in South India, spreading to Bengal under the Sena dynasty and Southeast Asia, as evidenced by 10th-century sculptures in Laos and Thailand. Comparatively, while Vaishnavite texts may prioritize Vishnu, Shaivite Puranas assert Sadashiva’s supremacy, as in the Shiva Purana where he is above the Trimurti.

In essence, the supreme revelation of Sadashiva’s first appearance, as chronicled in the Vedas and Puranas, illuminates the divine as an unchanging absolute from which all emerges. This understanding fosters profound devotion, inviting adherents to perceive the eternal through scriptural wisdom and ritual practice.