The designation Pashupati, translating to “Lord of All Beings” or “Lord of Animals,” constitutes one of the most venerable and multifaceted titles attributed to Lord Shiva within Hindu theological frameworks. Originating from the Sanskrit terms pashu, which encompasses all sentient beings bound by the fetters of ignorance and worldly attachments, and pati, denoting a sovereign protector or master, this epithet encapsulates Shiva’s dual function as both the binder of souls in the cycle of existence (samsara) and their ultimate liberator through divine grace. In Shaiva philosophy, pashu extends beyond mere animals to symbolize all embodied souls ensnared by pasha, the metaphorical nooses of maya (illusion), karma (actions), and anava mala (egoistic impurity). Shiva, as Pashupati, eternally oversees this cosmic dynamic, severing these bonds to bestow moksha (liberation). This article delineates the multifaceted origins and perpetual establishment of Shiva’s lordship over all beings, drawing upon archaeological evidence, Vedic scriptures, Upanishadic philosophy, Puranic narratives, Agamic texts, historical developments, and contemporary devotional practices to provide a thorough exposition.

Article Structure

Archaeological Evidence: The Proto-Shiva Figure and Indus Valley Antecedents

The genesis of Shiva’s association with lordship over beings can be traced to prehistoric archaeological artifacts, particularly those from the Indus Valley Civilization (approximately 3300-1300 BCE, with peak maturity around 2600-1900 BCE). The most emblematic artifact is the Pashupati Seal (Seal No. 420), unearthed at the Mohenjo-daro site in present-day Pakistan during excavations led by Sir John Marshall in the 1920s. This small steatite seal, measuring about 3.56 cm by 3.53 cm, features a central horned figure seated in a cross-legged yogic posture (mulabandhasana), flanked by four animals: an elephant, a tiger, a rhinoceros, and a buffalo, with two deer positioned beneath the seat. The figure’s headdress, adorned with buffalo horns and possibly a central plant motif, along with its three-faced appearance (interpretable as trimukha, or three-faced), bears striking resemblances to later Shaiva iconography.

The Pashupati Seal from Mohenjo-daro, illustrating the central yogic figure surrounded by animals.

A magnified view of the seal, accentuating the horned headdress and animal motifs.

An interpretive reconstruction highlighting the figure’s meditative pose and surrounding fauna.

Scholars such as Marshall posited this as a proto-Shiva, specifically as Pashupati, due to the evident dominion over animals (pashu), symbolizing mastery over the natural world and primal instincts. The figure’s possible ithyphallic state further aligns with Shiva’s fertility and ascetic aspects. While some contemporary archaeologists, like Gregory Possehl, caution against direct equivalence due to the absence of explicit textual corroboration from the undeciphered Indus script, the iconographic continuity with Vedic and post-Vedic representations is compelling. Additional seals from sites like Harappa depict similar yogic figures with animal entourages, suggesting a widespread cult of a deity governing life forms.

Transitioning to the early historical period, the Gudimallam Lingam from Andhra Pradesh, dated to the 3rd-1st century BCE during the Shunga or early Satavahana era, represents the oldest extant anthropomorphic depiction of Shiva. This phallic stone sculpture, standing about 1.5 meters tall, features a realistic human figure of Shiva carved on the lingam shaft, holding an axe and a water pot, with a dwarf (apasmara) underfoot symbolizing ignorance. This artifact solidifies Shiva’s role as Pashupati by portraying him as a transcendent guardian over bound entities.

These archaeological findings indicate that Shiva’s lordship over beings predates formalized Vedic literature, likely emerging from syncretic pre-Aryan and Dravidian traditions that amalgamated with Indo-Aryan elements.

Vedic and Upanishadic Foundations: Rudra’s Sovereignty Over Pashus

In the Vedic corpus, Shiva manifests as Rudra, a deity of awe-inspiring power, and the title Pashupati is explicitly invoked. The Rigveda (circa 1500-1200 BCE), the oldest Veda, contains hymns to Rudra that foreshadow his dominion. For instance, Rigveda 2.33.11 beseeches Rudra as the protector of bipeds and quadrupeds, imploring him not to harm “our cattle and our horses.” This establishes Rudra’s oversight of all living creatures, both human and animal.

The Yajurveda, particularly the Taittiriya Samhita (4.5.1-11), narrates the myth where Rudra, enraged by exclusion from a sacrifice, demands recognition as Pashupati. In this account, the gods offer Rudra the remnants of the oblation, acknowledging his lordship over pashus to appease him. The Sri Rudram (also known as Rudradhyaya) from the Yajurveda further extols Rudra with the mantra “Namaḥ pashūnām pataye,” saluting him as the lord of beings. This hymn, comprising 11 anuvakas, portrays Rudra as omnipresent in nature, residing in trees, rivers, and animals, thus affirming his eternal guardianship.

Advancing to the Upanishads, the Shvetashvatara Upanishad (circa 400-200 BCE) provides a philosophical deepening of this concept. In Chapter 3, Verse 1, it declares Rudra as the sole lord without a second, who rules over all worlds through his powers. Verses 4.13-18 elaborate: “He who is the lord of all bipeds and quadrupeds, the protector… the divine one who binds and releases.” Here, Pashupati’s role is metaphysical, Shiva eternally binds souls to the material realm via maya but offers liberation through knowledge of his true nature. The Atharvasiras Upanishad similarly identifies Rudra as Pashupati, stating that he pervades all beings as their inner controller, unchanging and eternal.

These texts transition Rudra from a Vedic storm god to a supreme ontological principle, where his lordship is not acquired but inherent, existing from the dawn of cosmic manifestation.

Mythological Episodes Conferring Eternal Lordship

The Puranas, composed between the 3rd and 16th centuries CE, furnish elaborate myths that dramatize Shiva’s attainment of Pashupati status, portraying it as both a divine achievement and an eternal truth. A central narrative is the Tripura Samhara (Destruction of the Three Cities), detailed in the Shiva Purana (Rudra Samhita, Section 2, Chapters 32-39) and the Matsya Purana (Chapters 128-130). Three demon brothers, Taraka’s sons, construct impregnable flying cities of gold, silver, and iron, terrorizing the gods. The devas beseech Shiva, who agrees to intervene only if granted absolute lordship over all beings, including themselves. Upon their assent, Shiva mounts a chariot formed from the earth and heavens, wields the Pinaka bow empowered by Vishnu as the arrow, and annihilates the cities in a single shot. This act eternally cements his title as Pashupati, as he now controls all pashus, demons as embodiments of tamas (ignorance), gods as sattva (goodness), and humans as rajas (activity).

Another poignant legend appears in the Skanda Purana’s Nepala Mahatmya (Chapters 1-5), set in the Himalayan region. Shiva and Parvati, weary of Kailasa’s interruptions, transform into deer and roam the Śleṣmātaka forest near the Bagmati River. When the gods, facing chaos in Shiva’s absence, locate him and grasp his horn in desperation, it fragments into twelve jyotirlingas. Shiva then vows to remain there eternally as Pashupatinath, the protector of all beings in their vulnerable forms. This myth underscores his compassionate assumption of lordship, manifesting in the physical lingam worshipped at the Pashupatinath Temple in Kathmandu.

The Varaha Purana (Chapter 215) and Vamana Purana (Chapter 45) echo similar themes, where Rudra petitions Brahma for the boon of pashu lordship to facilitate universal dissolution and renewal. These stories collectively illustrate that while Shiva’s lordship appears “attained” through narrative events, it is fundamentally timeless, reflecting the Puranic method of conveying profound truths via allegory.

Pashupata and Shaiva Siddhanta Doctrines

In advanced Shaiva schools, Shiva’s role as Pashupati acquires profound soteriological dimensions. The Pashupata Shaivism, founded by Lakulisha (circa 2nd century CE) and expounded in the Pashupata Sutras, views the universe as comprising pati (lord), pashu (souls), and pasha (bonds). Shiva, as Pashupati, eternally performs the five acts (panchakritya): creation (srishti), preservation (sthiti), destruction (samhara), obscuration (tirobhava), and grace (anugraha). The last two are pivotal, obscuration binds souls to illusion, while grace liberates them via initiation (diksha) and knowledge.

Shaiva Siddhanta, as articulated in texts like the Mrigendra Agama and Kiran Agama (circa 5th-10th centuries CE), elaborates that Pashupati resides in the sadakhya tattva (pure realm), overseeing 36 tattvas (principles of existence). Souls, as eternal pashus, are inherently pure but veiled by impurities; Pashupati’s lordship manifests through mantras and rituals that dissolve these veils.

Kashmir Shaivism, in works such as Abhinavagupta’s Tantraloka (10th century CE) and the Shiva Sutras (attributed to Vasugupta, 9th century CE), interprets Pashupati’s dominion as a divine play (lila) of concealment and self-recognition. Shiva, as pure consciousness, voluntarily assumes the role of lord to enable souls to realize their unity with him, thus “becoming” Pashupati eternally through spanda (vibration) and svatantrya (freedom).

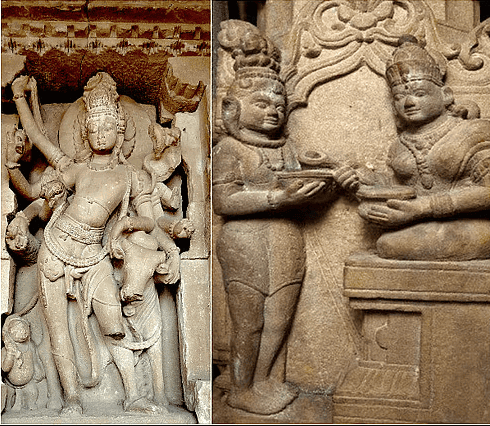

Evolution: From Mukhalingas to Monumental Temples

Iconographically, Pashupati’s form evolves from abstract lingams to elaborate representations. The five-faced (panchamukha) Sadashiva embodies comprehensive lordship: Sadyojata (creation, west, earth-like stability), Vamadeva (preservation, north, water-like flow), Aghora (destruction, south, fire-like intensity), Tatpurusha (obscuration, east, air-like subtlety), and Ishana (grace, upward, ether-like transcendence). This pentadic structure symbolizes dominion over the five elements and senses.

The Elephanta Caves’ Maheshamurti (5th-6th century CE, Kalachuri period) presents a colossal three-faced relief (implying five), with the central Tatpurusha face radiating serenity, the left Aghora evoking ferocity, and the right Vamadeva conveying femininity and grace.

Historically, Pashupati worship spread during the Gupta Empire (4th-6th centuries CE), with inscriptions at sites like Udayagiri Caves referencing Shiva as lord of beings. By the medieval period, temples like Pashupatinath (rebuilt in the 17th century on ancient foundations) and regional variants in Gujarat and Tamil Nadu perpetuated this cult. In Southeast Asia, Angkorian Khmer art (9th-13th centuries) depicts Shiva-Pashupati, indicating cultural diffusion via trade and migration.

Devotional and Cultural Perpetuity: Rituals and Modern Relevance

Devotionally, practices like the Pashupata Vrata, a rigorous ascetic regimen involving ash smearing, laughter, and meditation, invoke Pashupati for liberation, as prescribed in the Atharvasiras Upanishad. Festivals such as Maha Shivaratri celebrate his eternal lordship through vigils and offerings.

In contemporary contexts, the Pashupatinath Temple, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, attracts pilgrims worldwide, serving as a living testament to Shiva’s enduring role. Environmental interpretations link Pashupati to ecological stewardship, as lord of animals, aligning with modern sustainability discourses.

In summation, Shiva’s establishment as Pashupati, rooted in ancient artifacts, Vedic invocations, Upanishadic metaphysics, Puranic myths, philosophical doctrines, and historical icons, affirms his perpetual sovereignty as the compassionate master who eternally binds and frees all beings, guiding them toward ultimate realization.