In the profound depths of Hindu cosmology, time, known as kala, is not an abstract or independent entity but a dynamic force intricately linked to the divine essence of Lord Shiva. Revered as Mahakala (the Great Time) and Kalakala (the devourer of time), Shiva embodies the ultimate controller who transcends, originates, and governs temporal cycles. Far from being subject to time’s erosion, Shiva exists beyond its grasp, manifesting it as an extension of his cosmic will. This metaphysical truth, articulated across ancient scriptures, reveals time as emerging from Shiva’s eternal consciousness, driving the rhythms of creation (srishti), preservation (sthiti), and dissolution (samhara). The following examination draws upon Vedic hymns, Upanishads, Puranas, Agamic texts, philosophical doctrines, and iconographic traditions to unravel this mystery, highlighting Shiva’s timeless sovereignty and its implications for human liberation.

Article Structure

Rudra and the Embryonic Concept of Time

The foundational Vedic texts (circa 1500-500 BCE) introduce Shiva through his archaic form, Rudra, associating him with transformative forces that prefigure time’s destructive and regenerative aspects. The Rigveda, the oldest Veda, contains hymns portraying Rudra as a stormy deity of awe, whose arrows symbolize inevitable change akin to time’s passage. In Rigveda 7.46, Rudra is invoked as the protector and healer, yet his ferocity mirrors time’s inexorable consumption of all phenomena.

A more explicit linkage appears in the Atharvaveda’s Skambha Sukta (10.8), where the cosmic pillar (skambha), interpreted in Shaiva traditions as Shiva’s linga, supports the universe, encompassing past, present, and future. Verses describe the supreme being as existing before time’s manifestation, with Prajapati (often equated with Rudra-Shiva) as the source from which temporal divisions arise.

The Yajurveda’s Taittiriya Samhita and the Sri Rudram (Namakam and Chamakam sections) further elevate Rudra as omnipresent, pervading seasons, days, and nights, elements of cyclical time. The mantra “Kālāya namah” salutes Rudra as time itself, indicating that time originates as a facet of his divine power rather than a separate principle. These Vedic allusions establish time not as primordial but as subordinate to Shiva’s eternal nature, setting the stage for later elaborations.

Shiva as the Timeless Substratum

The Upanishads, philosophical extensions of the Vedas, crystallize Shiva’s transcendence over time. The Shvetashvatara Upanishad (circa 400-200 BCE), a cornerstone of Shaiva monotheism, declares Rudra-Shiva as the singular lord: “There is one Rudra only; he has no second” (3.2). Verse 1.10 describes him as the wielder of maya, projecting the universe’s manifold forms, including time, space, and causation. Verse 6.16 affirms: “He is the source of time, possessing all powers, the knower of all.”

The Kaivalya Upanishad equates Shiva with attributeless Brahman, stating in Verse 6: “He is Brahma, He is Shiva, He is Indra… He is the past, present, and future.” This underscores time’s illusory projection upon the unchanging reality embodied by Shiva. Similarly, the Mahānārāyaṇa Upanishad invokes Shiva through Panchakshara mantras, associating his five faces with mastery over the five elements and temporal flows.

In Advaita Vedanta interpretations, influenced by Shaiva thought, time (kala) is one of the modifications of maya, veiling the timeless Atman. Knowing Shiva as this substratum dissolves temporal bondage, granting kaivalya (isolation in eternity).

Time’s Emanation and Shiva’s Supremacy

The Puranas (3rd-16th centuries CE) provide vivid mythological frameworks for time’s origin from Shiva. The Shiva Purana (Vidyesvara Samhita) describes Shiva as Anadi (beginningless), from whose meditative trance emerges the cosmic egg, containing primordial time. During maha-pralaya (great dissolution), Shiva as Mahakala withdraws time, absorbing the universe into himself before exhaling a new cycle.

The Linga Purana narrates the infinite Jyotirlinga manifestation, where Shiva’s boundless form transcends temporal limits, humbling Brahma (associated with creation) and Vishnu (preservation). Time, personified as a force searching for Shiva’s origin, fails, affirming his precedence.

Fierce forms like Kalabhairava in the Kalika Purana and Skanda Purana depict Shiva enforcing time’s laws, punishing those who defy dharma with temporal suffering, yet remaining immune. The episode of Markandeya, where young sage clings to the linga as Yama’s noose (symbolizing death and time) approaches, illustrates Shiva’s intervention: emerging as Kalantaka (ender of time), he vanquishes Yama, granting Markandeya eternal youth. This myth symbolizes time’s subjugation to Shiva’s grace.

Cross-sectarian texts like the Bhagavata Purana acknowledge Shiva’s role in dissolution, where time (kala) acts as his agent but originates from his will.

The Eternal Dance: Nataraja and Temporal Rhythm

Central to understanding time’s origin is Shiva’s cosmic dance, the Tandava. As Nataraja, Shiva performs this in the golden hall of Chidambaram, symbolizing the universe’s pulsation. The Unmai Vilakkam and Agamic texts describe the damaru’s sound as nada (primordial vibration), birthing time-space continuum.

The 108 karanas (dance postures) in the Natya Shastra (attributed to Bharata Muni) mirror cosmic processes. Rudra Tandava destroys illusions, initiating new temporal eras. Chola bronzes (9th-13th centuries CE) depict Nataraja encircled by prabha-mandala (flame ring), representing time’s cycles; his matted locks hold the Ganga (flowing time) and crescent moon (lunar phases); the dwarf Apasmara beneath his foot signifies crushed ignorance, freeing souls from time’s wheel.

Ravana’s Shiva Tandava Stotram poetically captures this: “When you dance to shake the universe, the time stops in awe.”

Time in Shaiva Schools

Kashmir Shaivism (9th-11th centuries CE), through Abhinavagupta’s Tantraloka and Kshemaraja’s Pratyabhijnahrdayam, views time as Shiva’s shakti in sequential form (kramashakti). From timeless para state, Shiva voluntarily manifests parapara (time-space) for lila. Time is thus a self-imposed limitation, dissolved in recognition (pratyabhijna) of unity with Shiva.

Shaiva Siddhanta, in texts like Mrigendra Agama, classifies time as a tattva under Shiva’s Panchakritya, binding pashus via kala tattva but liberated through anugraha.

Hindu time scales, yugas (ages), manvantaras (epochs), kalpas (eons), culminate in Brahma’s day (4.32 billion years), dissolved by Shiva, emphasizing cyclical yet Shiva-centric temporality.

Mahakal Historical and Iconographic Contexts

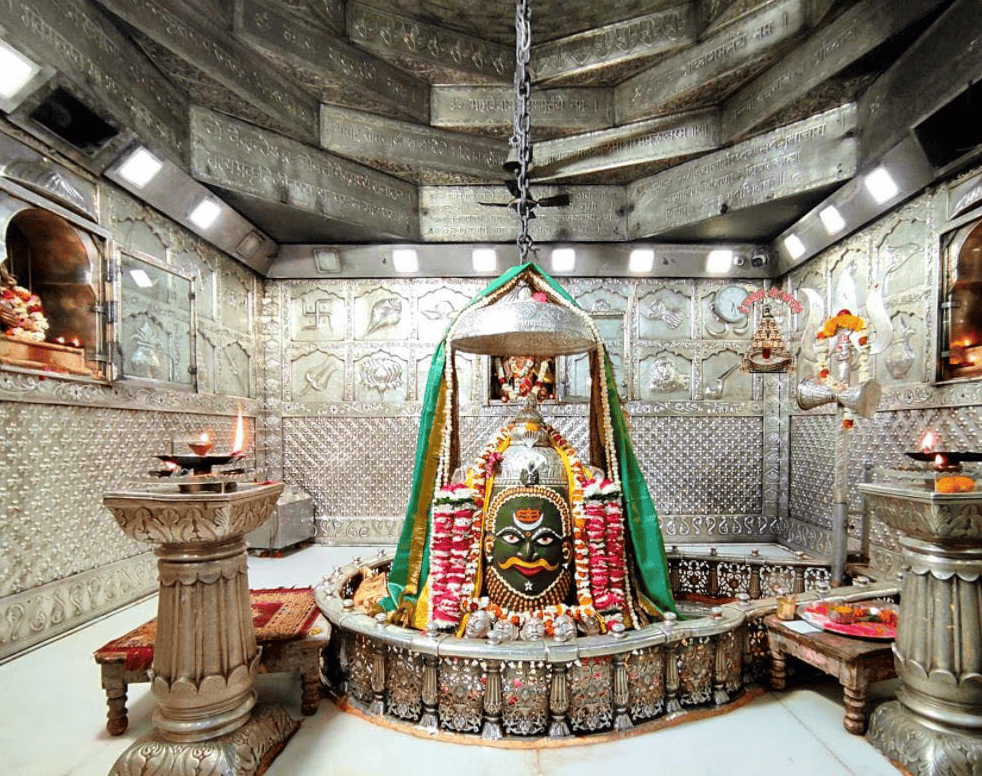

Historically, Mahakala worship flourished in Gupta (4th-6th centuries) and medieval periods, with temples like Ujjain’s Mahakaleshwar (one of 12 Jyotirlingas) timing rituals to conquer time’s fear. Iconography evolves from Vedic abstractions to anthropomorphic forms: Mahakala with skull garlands, trampling time-personified figures; Nataraja’s four arms holding fire (dissolution) and drum (creation).

Devotionally, mantras like “Om Tryambakam Yajamahe” seek freedom from time’s cycle of death-rebirth.

In essence, the mystery resolves in Shiva as time’s origin and transcendence: from his eternal essence flows kala, sustaining yet illusory before his grace. This scriptural wisdom, spanning millennia, guides seekers toward realizing the timeless self amid impermanence.