The figure known today as Śiva (Shiva) does not appear suddenly or fully defined in the earliest layers of Indian religious literature. Instead, Shiva emerges through a long process of linguistic use, ritual accommodation, and philosophical reinterpretation that unfolds over several centuries. In the Vedic texts, the word “śiva” first appears as a descriptive term, not as the name of an independent deity. Its gradual association with the god Rudra forms the foundation of what later develops into the Shaiva tradition.

To understand Shiva’s origins clearly, you must separate early Vedic evidence from later Puranic mythology. This article examines the etymology of the word “śiva,” Rudra’s position in the Vedas, and the transition from a feared marginal deity to a metaphysical principle. The discussion relies on primary sources such as the Rigveda, Yajurveda, Atharvaveda, and the Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad, supported by established academic scholarship.

Article Structure

Linguistic Roots of the Word “Śiva”

The Sanskrit word “śiva” derives from verbal roots √śī or √śiv, which convey meanings such as auspicious, gracious, kind, or favorable. Standard Sanskrit lexicons, including the Monier-Williams Sanskrit–English Dictionary, record “śiva” primarily as an adjective in early usage. It describes conditions, actions, or beings associated with well-being rather than naming a specific deity.

In the Rigvedic corpus, “śiva” does not function as a proper noun. It appears as a qualifying term, often applied to forces that are otherwise dangerous or unpredictable. This pattern reflects a broader Vedic habit of addressing feared powers through favorable language in ritual speech (Jamison and Brereton, The Rigveda).

Over time, repeated association between Rudra and the adjective “śiva” causes the term to acquire theological weight. What begins as description slowly moves toward identity.

Rudra in the Rigveda: Position and Character

Rudra occupies a distinctive place in the Rigveda. He receives relatively few hymns compared to deities such as Indra or Agni, yet the tone of these hymns is unusually intense. Rudra is addressed with caution, restraint, and supplication rather than confident praise.

Rigveda 2.33, the primary hymn dedicated to Rudra, presents him as both destructive and healing in nature. He wields arrows that bring disease, yet he is also invoked as the greatest physician among the gods, capable of curing illness and restoring health (Rigveda 2.33.4-7; Griffith).

This dual role places Rudra outside the orderly sacrificial structure that governs most Vedic deities. He does not operate through predictable exchange. Instead, he represents forces that must be acknowledged and restrained.

Disease, Healing, and Fear in Vedic Thought

In Vedic understanding, disease is not treated as a purely natural condition. Illness reflects divine agency and cosmic imbalance. Rudra governs this domain directly. The Atharvaveda repeatedly associates Rudra with both the causing and removal of disease, reinforcing his role as a power that moves between harm and protection (Atharvaveda 2.27; Bloomfield).

This explains why Rudra inspires fear rather than devotion. The hymns seek his mercy not because he is morally benevolent, but because his power is uncontrollable. Appeasement becomes the primary ritual response.

It is within this context that the adjective “śiva” gains importance. By invoking Rudra as “śiva,” worshippers emphasize his favorable potential and attempt to redirect destructive force into protection.

“Śiva” as an Appeasing Term

The use of “śiva” in reference to Rudra represents a deliberate ritual strategy. Instead of confronting Rudra’s fearsome nature directly, Vedic hymns reframe him through auspicious language. This approach does not deny his destructive capacity. It acknowledges it while seeking restraint.

Several Rigvedic verses combine praise with requests for mercy, asking Rudra to spare children, livestock, and the wider community (Rigveda 1.114). In these contexts, speech itself functions as a tool of control. Language is used to shape divine behavior.

With repeated use, the pairing of Rudra and “śiva” becomes stable. The epithet gradually shifts from description to identity.

The Śatarudrīya and the Expansion of Rudra

A major shift appears in the Śatarudrīya hymn, preserved in the Taittirīya Saṃhitā of the Yajurveda (TS 4.5-4.7). Unlike earlier hymns that approach Rudra from fear, the Śatarudrīya systematically lists his presence across all parts of the world.

Rudra is acknowledged in forests, mountains, paths, rivers, villages, craftsmen, hunters, and marginal social spaces. This enumeration does not soften Rudra’s nature. It universalizes it. Rudra is no longer peripheral. He is present everywhere (Keith, The Veda of the Black Yajus School).

The repeated use of “namah” signals recognition rather than fear alone. Rudra is no longer treated as an external threat. He becomes part of the structure of reality.

Rudra and the Limits of Sacrificial Order

Despite this expansion, Rudra remains separate from central sacrificial gods. He is not closely linked to the fire altar or priestly hierarchy. His associations with wilderness, solitude, and marginal spaces persist throughout Vedic literature.

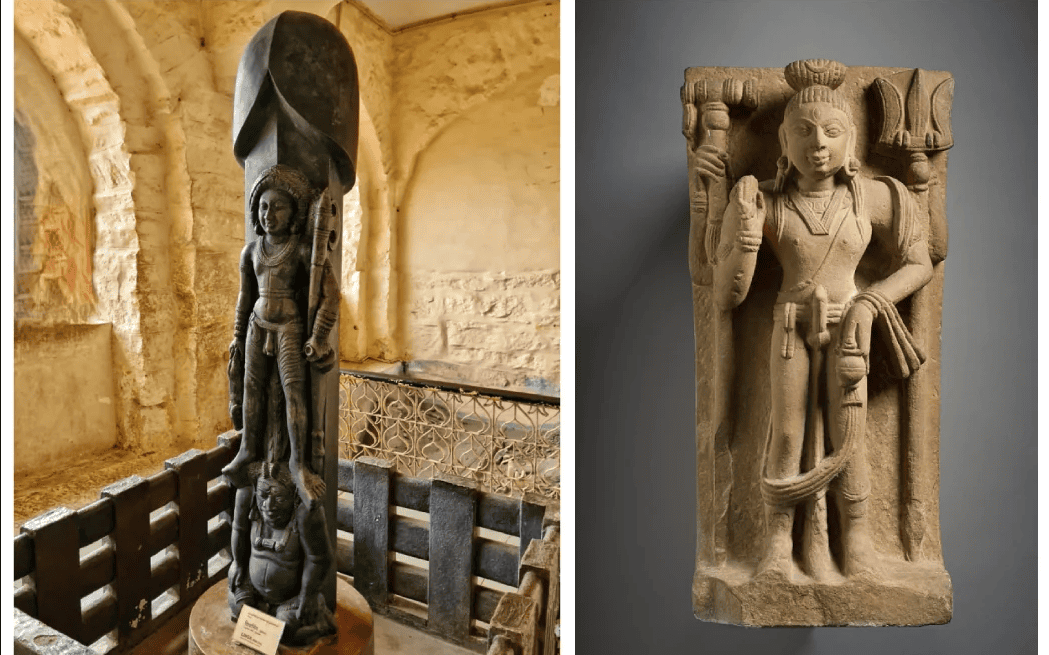

Epithets such as Kapardin, meaning one with matted hair, and Girīśa, the mountain-dweller, suggest an early ascetic or proto-renunciatory character (Rigveda 2.33). These traits later become central to Shiva, though they are not yet fully developed in the Vedic period.

Indigenous and Non-Vedic Elements

Many scholars argue that Rudra incorporates elements from pre-Vedic or indigenous religious traditions. His animal associations, wilderness domain, and lack of clear Indo-European parallels support this view (Michaels, Hinduism: Past and Present).

Rather than simple borrowing, this reflects synthesis. The Vedic tradition absorbs local religious elements by integrating them into its own symbolic framework. Rudra becomes a bridge between ritual religion and experiential spirituality.

Upanishadic Reinterpretation of Rudra–Śiva

The Upanishads mark a clear philosophical shift. Ritual performance gives way to metaphysical inquiry. Within this framework, Rudra undergoes a decisive transformation.

The Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad identifies Rudra as the supreme reality, declaring him the sole ruler of the cosmos and the source of all beings (Śvetāśvatara Upaniṣad 3.2-4; Olivelle). Here, Rudra is no longer one god among many. He is Brahman itself.

At this stage, “Śiva” no longer functions as an appeasing adjective. It denotes the essential nature of reality.

Names and Epithets as Historical Markers

The multiple names associated with Shiva represent distinct historical layers. Rudra reflects the earliest Vedic phase. Śiva emerges as an auspicious reframing. Paśupati suggests pastoral and animal symbolism. Mahādeva reflects elevation within an expanding theistic framework. Śaṅkara emphasizes benevolence.

These names accumulate rather than replace one another. Each preserves a specific stage in Shiva’s theological development (Kramrisch, The Presence of Śiva).

What Vedic Texts Do Not Describe

Vedic literature does not describe Mount Kailasa, Parvati, Nandi, or explicit lingam worship. These elements belong to later Puranic and sectarian traditions.

Projecting later imagery back into Vedic texts distorts historical understanding. The Vedic Rudra–Śiva forms a conceptual foundation, not a complete mythological system.

Conclusion: Shiva as a Developing Idea

The origins of Shiva in Vedic literature reveal a process rather than a single moment of origin. From the feared Rudra of the Rigveda to the metaphysical absolute of the Upanishads, Shiva develops through language, ritual practice, and philosophical reflection.

This gradual evolution explains why Shiva resists simple definition. He embodies destruction and healing, fear and protection, withdrawal and universality. Understanding his Vedic roots allows you to see Shiva not as a fixed figure, but as one of the most durable and integrative ideas in Indian intellectual history.